UNHS News & Events

How a Navajo Nation Health Worker is Treating America’s Worst Covid-19 Outbreak

- By unhsinc

- January 15, 2021

- No Comments

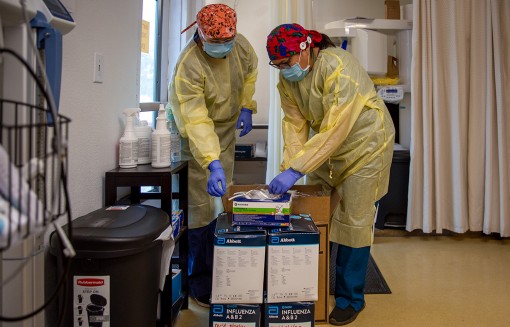

Yazzie, 31, is one of eight women helping run the health clinic in Navajo Mountain, a chapter of the Navajo Nation that straddles the border of Arizona and Utah. Photography by Sharon Chischilly for Elemental

Roxanna Yazzie works long hours to keep her community safe from Covid-19

Even in winter, when temperatures drop to below freezing and the dirt roads are coated in snow or ice, Roxanna Yazzie slings her clinic badge over her down jacket, pulls up the hood of her green jacket, and makes for work.

Yazzie, 31, is one of eight women helping run the health clinic in Navajo Mountain, a chapter of the Navajo Nation that straddles the border of Arizona and Utah. However centrally located Navajo Mountain appears on a map, it takes about two hours to drive to the nearest emergency room. In mid-March, the Navajo Nation was particularly hard hit by Covid-19, with cases peaking a month later. As of May, the nation had the highest Covid-19 infection rate out of any of the U.S. states. Approximately 500 people live in Navajo Mountain, Yazzie says, and the community lost a few elders to Covid-19 earlier on during the outbreak. Case numbers have come down since the spring, largely owing to masks, curfews, and weekend lockdowns. Even as cases spike across most of the United States, few people are testing positive for Covid-19 in Navajo Mountain, Yazzie says.

Before work, Yazzie is out of bed by 4:30 or 5:00 every morning. Some days, she first feeds her livestock, then she prepares breakfast for her husband and their three school-aged kids. She always makes a hot meal before she leaves for work — fry bread with potatoes, eggs, and bacon or ham. She skips breakfast herself. “For some reason, I can’t eat breakfast. I’m a coffee person, which gets me through the day,” Yazzie says.

A few minutes before 8:00, Yazzie leaves for work in her scrubs, after she gets her kids ready for their online classes. Her husband stays with the kids and helps with their distance learning. The clinic is just a short walk away. When she gets in, Yazzie puts on her PPE: N95 mask, face shield, gown, and gloves. Even though Covid-19 cases have gone down since the start of the pandemic and it’s becoming less common for the Navajo Mountain clinic to see patients with the virus, Yazzie still treats every patient like they might have it. “Even if they are coming in for leg pain, we always gear up, because we don’t know if that patient has been exposed,” she says.

At the clinic, Yazzie is the lab technician. After she arrives, she walks down the hall and she turns on the machines needed to run routine lab tests that measure immune cells, hemoglobin, and glucose. Then, she and others — including the doctor, medical assistant, and the woman working the front desk — meet for their morning huddle, as they discuss the schedule and patients for the day.

Working at a small clinic means that each health care worker often takes on many different roles. “We don’t just have one job,” Yazzie says. They have all been training each other. Yazzie now helps patients find specialists if they require more specialized help, which she wouldn’t ever ordinarily do as a lab technician. She sometimes takes a patient’s vitals or X-rays or helps wipe down surfaces for the next patient. If Nicole Thompson, who works the front desk, steps away, Yazzie will take her spot.

It’s frustrating when you see other people on the news complaining about the little stuff. We’re out here on the reservation making it work.

Throughout the day, Yazzie says patients are coming to the clinic for more routine needs: pain and body aches, diabetes, or pediatric checkups. Although the clinic mostly serves Navajo Mountain, folks who reside in other chapters of the Navajo Nation also get medical care there.

Every patient who comes to the clinic gets swabbed for Covid-19. Most of these tests are coming back negative, even in the winter months. The last positive test result was in November, according to Yazzie, although it’s possible other residents are getting tested at clinics throughout the Navajo Nation and are turning up positive there.

Yazzie and her colleagues at the clinic initially set up an outdoor tent for appointments, which minimizes the spread of the virus if the patient is indeed infected. However, when the tent collapsed during a snowstorm, the clinic found a spare trailer to set up for patients.

Around noon, the team breaks for lunch. “Sometimes we’ll have a 10- or 15-minute lunch break because we’ll have patients at 11:30 and noon, so we’ll hurry up, eat something, and get back to work.”

For the rest of the day, Yazzie continues with her assortment of tasks, running between different parts of the clinic and helping with phone calls, patient intakes, taking vitals, and running routine blood tests. The pace of work is sometimes busy, sometimes slow. “But we don’t like to say, ‘It’s slow today,’ because if we say [that], we’ll have a lot of people showing up out of nowhere,” she says.

Before the clinic closes for the day, Yazzie makes sure she’s completed the patient charts, wipes everything down with bleach, checks the schedule for tomorrow, and goes home. They used to be able to see more patients but are now limited to at most eight per day.

If patients come in at the end of the week and require a time-sensitive test, like a Covid-19 swab, Yazzie’s workday becomes significantly longer: She’ll be the one to drive it three hours to Blanding, Utah, where the test gets processed. At 4:30, when other health care workers are leaving, she hops into the clinic’s van. By the time she gets home from Blanding, her family will already be fast asleep.

Most days, however, when she gets home, her kids are excited to see her, but Yazzie has to stop them from touching her the second she walks in. “They act really happy. I’ll be like, ‘No, no. Wait until I shower and change my clothes.’” Only once she’s bathed will she let them give her a hug.

Yazzie says some of the biggest challenges of dealing with Covid-19 in Navajo Mountain are not providing care at the clinic and her community, but getting access to food and water that would allow her community to quarantine safely. (The Navajo Nation has, on occasion, instated 57-hour lockdowns over the weekends and is currently in the midst of a two-week lockdown order.)

“We don’t have stores near us at all,” Yazzie says. It takes four hours round-trip to make a grocery run at the nearest Walmart. If she wants to go to a wholesale store, she’ll be in the car for six hours to make a trip to Sam’s Club in Flagstaff. “When the pandemic first started, we would get to Walmart and all the meat was gone. I was frustrated, because I thought about the family that lived across the canyon: How are they going to come out and get food for themselves?”

Many families in Navajo Mountain don’t have running water, which makes it difficult to maintain good hygiene practices to stave off Covid-19. “Sometimes you have to wake up really early, at 3 a.m., just to get water at the windmill,” she says, which is 12 miles from the clinic. By then, the cars will already be lined up. That water is also used to feed the animals, wash hands, and store in kitchens for cooking.

“It’s frustrating when you see other people on the news complaining about the little stuff,” Yazzie says. “We’re out here on the reservation making it work.”

Despite the challenges of her work and constantly being away from her kids, she’s proud to serve her community. Earlier in the pandemic, Yazzie and her team would check on community members who were recovering from Covid-19, deliver food to elders, and make house calls to people who didn’t have access to a car.

“I’m proud of my team here,” Yazzie says, “of how we all work together and how we’re standing strong all the time.”